Unintended consequences: TEN-T expressways impeding the Western Pomeranian regional cycling network

Investments on the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) are often carried out without considering the needs and potential of active mobility, sabotaging the development of local and regional cycle routes. Wanda Nowotarska, the regional cycling officer in Western Pomerania, Poland, who oversees the development of a 1000-km long cycling network, provides a few concrete examples from her work.

The “Gryfino” interchange of the S3 expressway (Baltic-Adriatic TEN-T core corridor) and regional road number 120, completed in 2010, does not include any cycling infrastructure. Following the opening of a large workplace (Zalando) on the east side of the interchange, it has now become a major barrier for cycling traffic. Most of the employees commute from Gryfino, Wełtyń and Gardno – perfectly within cycling distance but on the other side of the expressway. The municipality of Gryfino is building a cycle track from the town to the S3 road, but a construction of a separate bridge over the S3 exceeds their financial capabilities. As a result, the ERDF-funded cycle path will end several hundred metres before a major workplace, on a dangerous barrier created by a TEN-T road, co-financed by the EU Cohesion Fund.

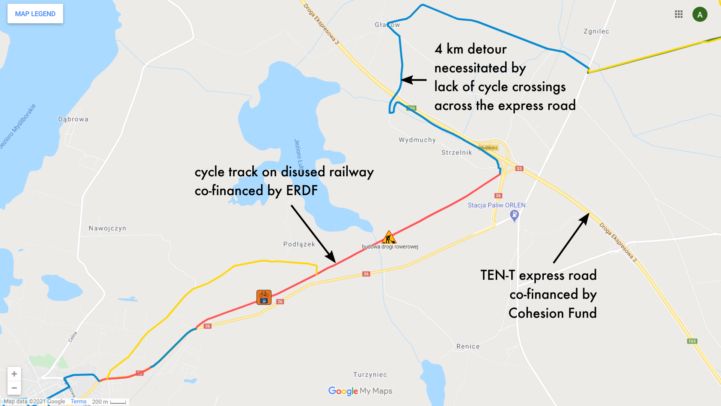

Another section of the S3 expressway, also completed in 2010, crosses the old track of the Stargard – Pyrzyce – Myślibórz – Kostrzyn railway line, and the interchange “Myślibórz” was built exactly on the old track. Large sections of the disused track have been already adapted for a touristic cycle route, but lack of provisions in the interchange area necessitates construction of a long cycle bridge and a detour of nearly 4 km. Moreover, the reconstruction of the dismantled railway line is currently planned. If the railway corridor had been preserved in the design of the S3 expressway, it would not only allow for a direct bicycle route but also for an easy reconstruction of the railroad.

Similarly, the bypass of Wałcz on the S10 expressway crosses the embankment of the Wierzchowo-Wałcz railway line, blocking the plans for national cycle route number 15. This bypass is part of the TEN-T comprehensive network, currently under construction, with completion expected by the end of 2020.

The bypass of Szczecinek on the S11 expressway, part of the TEN-T comprehensive network, was completed in 2019 at a cost of nearly €100 million, with co-financing provided by the EU Cohesion Fund. The project included a footbridge over the S11 and adjacent railroad line around the Szczecinek Chyże rail station. However, the bridge was designed for pedestrians only, without taking into account cyclists. As a result, the cycle route 20 had to be redirected to cross the S11 on a parallel county road – also with no cycling facilities.

Finally, the Kijewo interchange on the S6 expressway (Baltic-Adriatic TEN-T core corridor) in Szczecin, the capital of the region, does not include any bicycle infrastructure. In 2021, when the construction is completed, cyclists from the south-eastern part of the city will be completely cut off from the centre. There are no alternative asphalted roads. The region allocated funding to the city of Szczecin for the construction of a cycle route in a different corridor, but due to the requirements of the forest administration, this itinerary will not meet the requirements of commuters (no asphalt, no illumination).

Not all TEN-T projects were bad for cycling. On the section of the S6 expressway crossing Koszalin, opened in 2019, high-quality cycle tracks were integrated into two interchanges. The continuity of the popular cycle route along Morska street, connecting the city with the sea, was preserved in the Koszalin North interchange. Moreover, inclusion of a cycle track in the neighbouring Koszalin East interchange extended the pre-existing route along the Władysława IV street by 600 m, creating a functional cycle connection between the Jamno district and the centre of the city.

The barriers created by the TEN-T projects are complicated and expensive to overcome. On the bright side, the Western Pomeranian commitment to cycling network development made the national road administration see the cycling officer as a partner. The region’s relevant stakeholders will now be consulted for any new investments, reducing the probability of creating further barriers in the future.

On the European level, following two years of ECF lobbying, the recently revised Directive on Road Infrastructure Safety Management obliged the EU Member States to take the needs of cyclists in major road investments into account. We are currently working on incorporating the same principles in the upcoming revision of the TEN-T guidelines. When building or upgrading for example a major road or a railroad line, the potential for cycling along and across the planned investment should be systematically evaluated, and key elements, such as bridges and tunnels, integrated into the project. Find out more about the TEN-T and the ECF demands related to it on our TEN-T, EuroVelo and cycling webpage.

Author: Wanda Nowotarska